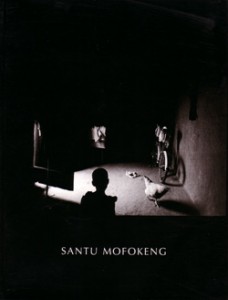

Santu Mofokeng was born in 1956 in Johannesburg. He began his photographic career informally as a street photographer in Soweto, and in the early 1980’s set out to pursue photography in earnest, mostly through documentary coverage of political activity at the time. Having won several awards, and staged numerous exhibitions in the interim, Mofokeng has become one of South Africa’s foremost photographers – one whose work re-situates the role of the medium in the country’s history. Engaging subjects as visually diverse as religious ritual, black middle-class identities, and the signifying potential of landscape, he upsets the comfort zones of racial and cultural memory, always foregrounding the ideological role of representation. Based in Johannesburg, Mofokeng works as a freelance curator, writer, researcher and photographer.

The book consists of 96 pages with 48 pages of duotone images. The text in this book entitled ” Lampposts” was written by Santu Mofokeng and has been translated into French (“Réverbères”) and Dutch (“Lantaarnpalen”). The second text,” Communities of Interpretation” is by Sam Raditlhalo.

Philippa Hobbs is the author for the educational supplement published with TAXI-004 Santu Mofokeng.

EXTRACT FROM THE BOOK

English:

Lampposts

“They suffer abuse mostly quietly, except maybe give a dull wooden thud or a metallic twang when struck. They provide illumination. They are viewed with suspicion by some, they are ignored by most. They are taken for granted. They are there to lean on or to piss on.

A lamppost stands directly in front of our house in the Orlando East of my youth. Every evening I would escape the gloom of our family room – dimly lit by candle and the blue and ember flames of the brazier fire, in which hangs the smog, the pungent smell of carbon monoxide, boiling cabbage or offal – to avoid the gaze of my elders, petty errands and dull adult conversation; in order to pursue the company and mischief of other children playing hide and seek by the street light. “Black maipatile” we called this game. Screaming “mee mmee!”, we would disappear into gardens of mielies, climb peach or apricot trees and hide behind the hedges until discovered. This frolic provided the opportunity to steal peaches or apricots. Sometimes we would try to screw the girls who followed us to our place of hiding, to the refrain, “I am going to tell.” I was about nine or ten. The games invariably ended before a quarter of eight, when we would run back to our different homes to huddle near um’sakazo, Zulu and Sotho rediffusion FM broadcasts. We’d listen to 15-minute instalments of “Raborikgwana” – a drama serial on the radio – after which we had our supper and bed. The SABC regulated our playing time more than any parent could.

There is Phumelangaphandle, which name we gave him and it translates literally thus: get-out of-the-house. He was my aunt’s lover. And there is Mdungazi, the Shangaan with yellow teeth. His one leg was gangrenous and we used to mock him whenever he laughed because of his rotten teeth. Our neighbour Sephara, a Royal reader by his own account, liked to tease my stepfather, ex-body builder and pianist, by calling him “wolf”. Mothobi, a war veteran who saw battle in Normandy and North Africa, entertained us with his military drills whenever he got drunk and went into a trance.

Commuter buses disgorged these and other workers on the outskirts of the township every night. The workers would then negotiate a grassveld, approach the street lamps on the periphery of the township, dispersing, sometimes in groups in the direction of their homes, some to the beerhalls, others to our home because my mother was a brewer. There was this lone tsotsi, a thug, who preyed on stragglers among the workers. He would come up behind, lob a dustbin over the head of the unsuspecting victim. Stunned, blinded, hands pinned to his sides by the bin, the poor victim’s pockets would then be emptied. He was a phantom, this attacker; nobody knew who he was until one of his victims, bin over his head, hands pinned to his sides, bolted. Caught completely by surprise, the thug gave chase – spontaneous reaction, surely. On reaching the perimeter of the township, the thug was identified. Needless to say his career was finished – Amadod’omzi, the civil guards, made sure of that.

In the day, the lamppost stands mostly ignored, taking the hot with the cold, the wind and the wet in silence. We children, armed with slingshots, hunting sparrows and pigeons, would often use the street lamp for target practice. Popping bulbs of the streetlights was accidental. It became a pastime for some. The municipal blackjacks, South Africa’s black Bobbies on the beat, had their hands full trying to capture these miscreants. I still maintain that the Johannesburg City Council relinquished the administration of the township in disgust, because they were unable to cope with the job of replacing broken bulbs.” […

DETAILS OF BOOK

Author : Brenda Atkinson

Editor: Brenda Atkinson

Design: Roelof van Wyk

Production: Anina Kruger, Chris Nathan

Publisher: David Krut Publishing

French Translator: Catherine Lauga du Plessis

Dutch Translator: Loes Nas

Printing: Keyprint

Paper: First Paper House, Ideal White Silk 150&250 gsm

ISBN 0-620-26401-2

© The authors, the artist, and David Krut Publishing, 2000

ENQUIRIES

TAXI-004: Santu Mofokeng, available through David Krut Publishing